|

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen We have, to date, failed to stop the runaway train of climate change. On this holiest day of the Jewish calendar, we must ask ourselves, How can we find and extract beauty from the pain of our failure? What does it take for us to put love, compassion, and hope at the center of our lives, and in the process transform both ourselves and the world around us into something far more beautiful than anything we have known before? Part of what it takes is determination and an unwillingness to give up. We can learn something about determination from mushrooms, which push their way up through whatever is needed in order for their fruiting bodies to reach the air. Photo credit: Katy Z. Allen We can learn something of determination from seedlings and from trees Photo credit: Mary North Allen We can learn something of determination from the history of the Jewish people. After the destruction of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem two millenia ago, the ancient rabbis refused to accept defeat, and transformed their religion into something that would work in the diaspora and without a central place of worship. It was out of the ashes of the destruction of the Temple that the Rabbinic Judaism we live today was born, a deep collective act of turning pain into beauty. We can learn something of determination from the rebirth of the Jewish people after the tragedy of the Holocaust. So many survivors refused to let their spirits die, but to go on living, and, each in his or her own way, to create.a small, perhaps imperfect, oasis of beauty, the essence of life. On this holy day, and every day, what keeps you determined to live with love, compassion, and hope? Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

0 Comments

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Like heat and like hope, love and compassion are also invisible. And like them as well, we can also feel them. We know when they are in the room with us. Alex Tait for Fine Acts Love and compassion are powerful tools in the journey from pain to beauty. They give us strength. They give us courage. They give us meaning. El Harachamim, G!d of Mercy, G!d of Compassion. HaRachaman, The Merciful One, The Compassionate One. These are names we give to That Which Is Beyond Our Comprehension, especially at this time of year when we are seeking forgiveness. It is a comforting vision of G!d that can help us forgive ourselves, which may often be the first step toward forgiving others, and toward turning pain into beauty. Compassion and love go hand-in-hand. We are commanded each day, You shall love the Holy One, your G!d, with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your might. Can we love because we are commanded to? Perhaps not. But reminding ourselves each day to love something we can't see or fully comprehend can also be a reminder to love ourselves, and each other. Love and compassion. Are you willing to risk them? Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Like heat, hope is invisible. And just as science can make the impact of heat visible, so can artists make the power of hope visible. In fact we all can. Violeta Noy for ArtistsForClimate.org Hope is hard to define. I always remember that hope and optimism are not the same thing. Many famous people and many faith traditions have a lot to say about hope. After spending time with many of these definitions and descriptions, I came to think of hope as a state of being, as something that is critical for us humans in order to stay alive. I understand making the effort to turn our pain into beauty, even when we don't fully succeed, as an act of hope, an expression of our hope, a statement that life can be better. Given the history of the Jewish people, I see living as a Jew as an act of hope. What does hope mean to you? How do you make hope visible in your life? Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

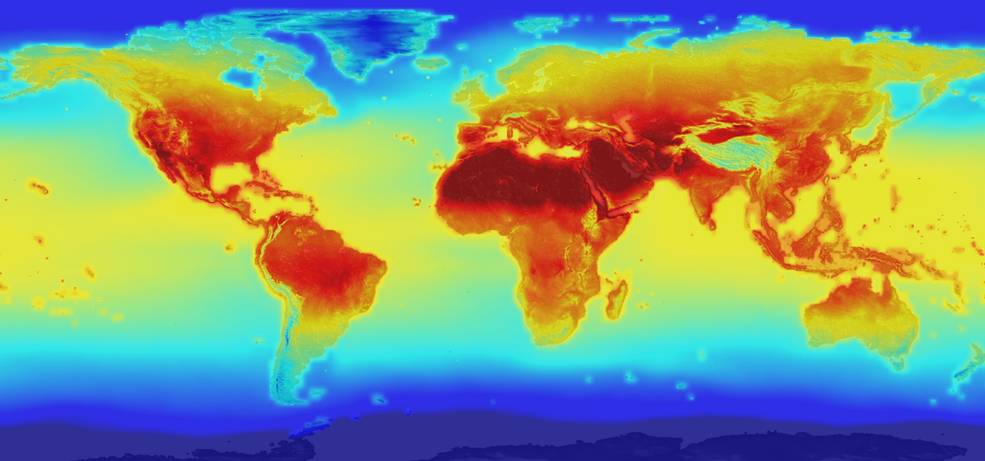

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen I do not do well in the heat. If I overdo it in warm weather, I can get really unpleasantly sick. But I am privileged. I don't have a job where I have to work outside in the sun no matter what the temperature. I have mini-splits in my home that provide low-energy-usage cooling that keeps me safely comfortable no matter how high the temperature outside. I am part of a distinct minority. As temperatures rise and records are broken year after year, the death toll from heat related causes continues to rise. Farm workers, people with schizophrenia, the elderly, and many others are at risk. The rate of suicide rises as temperatures increase. Wildfires become more likely. The situation is deadly. Beyond the impact on humans, rising global temperatures impact species distribution. Species are shifting toward the poles and higher elevations. Extinction rates are increasing. These changes in turn impact other aspects of ecosystems, such as their ability to store carbon. The web of impact expands. High heat is invisible to us. It doesn't in and of itself have physical beauty. But scientists can make its presence beautiful though thermal maps. It is a painful beauty. Photo credit: NASA Lots of other things are invisible too. Emotional pain, but also love. Hurt feelings, but also compassion. Anger, but also forgiveness. How do we make our love, our compassion, and our forgiveness visible to those around us? When we do so, we turn the pain in our hearts to beauty. May we find the strength, the courage, and the determination to turn our invisible pain into visible beauty. Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Purple loosestrife is beautiful. It’s vivid purpureal spikes are striking and readily attract our attention. Photo credit: Katy Z. Allen But purple loosestrife is an allelopathic plant, when growing in the wrong place, it makes it hard for other plants to survive. It becomes bossy and takes over. Photo credit: Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org Before I knew about purple loosestrife’s aggressive tendencies, I simply enjoyed its beauty. Now it’s more complicated. Now, the pain of it’s impact is always combined with its beauty whenever I see it growing in the wetlands near my home. Now purple loosestrife, like so many other beautiful flowers that are damaging ecosystems, is calling out to me to allow the dynamic of holding pain and beauty at the same time to transform me. I don't always want to hear that message. Yes, I believe that only by seeing the danger and suffering in the beauty can we fully experience all the emotions that climate change and environmental destruction engender within us. And only by experiencing all these emotions can we be fully transformed, and thereby bring positive transformation into the world. Can we accept the challenge to do this? Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Gazing into a campfire is mesmerizing. The flames are constantly moving, shifting, dancing, leaping up, dying down. The coals glisten, brighten, darken. The fire holds memory and ancient connections to our earliest human hunter-gatherer ancestors. Vivid images rise up, of shaggy-haired men and women wearing primitive animal skin clothing sitting around a roaring fire that warned off potential predators and ripping off chucks of roasted game meat from the bone with their teeth to feed themselves. Fire was critical for the survival of ancient humans and for the development of civilization. But despite all our technological advances, fire remains critical to us today. Even in our modern, highly developed societies, fire is needed to provide heat to protect us from the cold of winter and, albeit often in less “primitive“ forms, to make it possible to cook our food. Fire is also fearsome and dangerous, and in our climate-changed world it is ravaging forests and towns, indiscriminately killing plant life and wildlife, and human life as well. USFS/Mike McMillan Despite their fearsomeness, like a campfire, raging wildfires are mesmerizing, turning their past and potential future pain to beauty in vivid hues of orange and red and black. And once the fire is gone and even just a short time has passed, the landscape slowly transforms. It springs back to life with new growth, giving rise over time, to a rich new ecosystem of thriving more-than-human life. USFS/Dorit Buckley The natural world is programmed to turn the pain of wildfires into a new generation of beauty. What does it take for us to do the same? Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Growing up in the Upper Midwest and living since then in the Northeast, I have many memories of intense snowstorms, some of them blizzards, as well as less frequent ice storms. Both left death and disruption in their wake. During such storms, electric power distribution often fails, and hundreds of thousands of people can be without heat and electricity for days on end, making life inconvenient at best and life threatening at worst. This past December's Category 4 storm that crippled Buffalo and other parts of the northern US killed 106 people and left more than $8 billion in damage and more than 7 million people without power. Increasing amounts of moisture in the air due to climate change is increasing the severity of storms, even when it’s cold, by making heavy precipitation more likely and more frequent, thus increasing the disruption and death. Photo by Mary North Allen And yet, once such a storm is over and the Sun comes out, the world is transformed into a bright and glittering fairy land. The power may still be out, search and rescue teams may still be at work, and the danger may not be over, but the beauty of the snow-covered landscape can be breathtaking. The world has been transformed. Photo by Mary North Allen The question arises, what does it take each of us to transform the bit of the world that is within and around us to something breathtakingly beautiful? To take a step in that direction is the task of these days, and our lives. Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen G!d called the dry land Earth and called the gathering of waters Seas. And G!d saw that this was good. --Genesis 1:10 It takes only a few days to die of thirst. The Native American water protectors mantra, "Water Is Life", is very real. Our adult bodies are about 60% water. We literally cannot live without water. But the saying, "Water, water, everywhere and not a drop to drink," from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's famous Rime of the Ancient Mariner, is equally true. Salt water and once-fresh water filled with toxic pollutants do our bodies no good. We are not alone in our need for water. Life in, on, and above the Earth cannot survive without water. Space exploration of planets and moons seeks out the presence of water as a measure of the possibility of life. With drought, plants shrivel and die and animals migrate or die as well. A lack of enough clean water is a death knell for living beings of all kinds. About 2 billion people around the world suffer from safe water scarcity. The reverse, too much water, can also kill. Hundreds of people die from flooding every year. Hurricanes, extended downpours, and rising sea level are all threats to life as we know it. The blooming of the desert is a known spectacular response to rain in arid parts of the world. A small amount of rainfall works magic, springing long-waiting plants to life, always at the ready to begin the cycle of flowering and seed production when moist conditions arise. In other places, flooding of river plains enriches the soil, making these areas especially fertile grounds. Photo by Mary North Allen Nature has evolved to bring the beauty of new growth after too little or too much rain. How do we, too, bring the beauty of new growth, new ideas, new connections, and new courage into our drought-stricken or inundated lives? This is our daily task, our life work, in this climate changing world in which we live. Photo by Mary North Allen Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah.

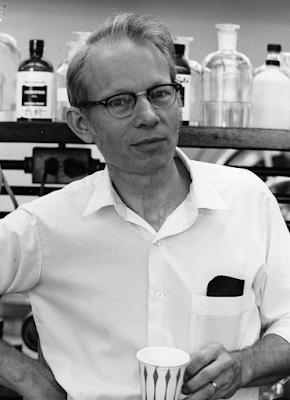

by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Failure can be so painful. A defeat. A measure of our worthlessness. An embarrassment. A time to bury our heads in the sand. A time to weep. Failure can fill us with despair. But failure can also be an opportunity. It can open doors to new possibilities. It can bring motivation to go deeper. My father was a scientist and early in his career, he had a massive failure with his prime experiment. His colleagues expected him to move onto something else. But he didn’t. He spent his life searching for, and eventually finding, answers to the questions created by his experiment’s failure. He turned his pain into beauty. I made a mistake when planning this year’s Earth Etudes for Elul. I counted wrong. I didn’t have a space left for my own etude.

I despaired. I considered putting two together on one day. And then I decided I needed to take responsibility for what had happened, to step back and not write an etude this year. Before I knew it, the space left open in my mind and soul suddenly filled with the thought of writing for the 10 Days of Repentance, and the idea of this project germinated and began to grow. It is now blossoming, and over the coming days, I hope you will agree that I succeeded in turning my pain and embarrassment into beauty. What failures have you experienced recently? How can you turn them upside down and see them as opportunities? How have you done this in the past? What can your experience teach you? May our eyes be opened to the unexpected possibilities presented by our failures, and in the process bring new beauty into the world. Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah. by Rabbi Katy Z. Allen Photo: Mary North Allen The challenge in life is to figure out how to turn our pain into beauty. My mother, z"l often spoke of the challenge of dealing with pain as she navigated a life marked by trauma and mental crises, as well as profound and beautiful artwork and deep friendships. My brother, a gifted musician, repeats these words often. And lately, long after my mother's passing, they have been resonating strongly with me, informing my life.

As we celebrate the New Year and enter Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe, and the 10 Days of Repentance, one of the two most intense times in the Jewish calendar, I invite you to journey with me through an exploration of turning pain into beauty. As you light the candles to welcome Rosh Hashanah, eat apples dipped in honey to symbolize our desire for a sweet and good year, I invite you to meditate on how these simple traditional rituals are transforming something difficult within you into beauty and hope. Consider the questions: What pain do you carry? How do you or might you transform that pain into beauty? What is beauty and what does it mean to you? How does transforming your pain into beauty bring you closer to the Holy One of Blessing? How can you express and articulate this process? What related questions bubble up? As we journey together through these Ten Awe-Filled and Potentially Transformative Days, may all of your questions spiral through you and give life to a renewed state of forgiveness. Rabbi Katy Allen is the founder and rabbi of Ma'yan Tikvah - A Wellspring of Hope, which holds services outdoors all year long and has a growing children’s outdoor learning program, Y’ladim BaTeva. She is the founder of the Jewish Climate Action Network-MA, a board certified chaplain, and a former hospital and hospice chaplain. She received her ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, NY, in 2005. She is the author of A Tree of Life: A Story in Word, Image, and Text and lives in Wayland, MA, with her spouse, Gabi Mezger, who leads the.singing at Ma'yan Tikvah. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed